Off the back of last month’s article, I explore how individuals in aviation are (or aren’t) sticking to the industry-wide emissions pledges, and developing their own methods of making aviation more sustainable.

November has been a pretty eventful month for the aviation industry. Between the Dubai Airshow and airlines vying for the ‘best’ post-pandemic measures to get the ball rolling again, there’s been an awful lot of news to cover. So, I wouldn’t blame some of you for thinking there might be more important things to talk about than the ongoing process of making aviation more sustainable. ‘Not another long, rather factually dense article about green flying,’ I hear you cry. Well, I’m afraid it is. But don’t despair, part two of Green Flying aims to give you an inside look at the cutting-edge technology being developed by the industry, as well as exposing how a lot of the measures outlined in part one are being avoided by big players in aviation. Scandals and new tech – what more could you want in an article?

A Key Alliance

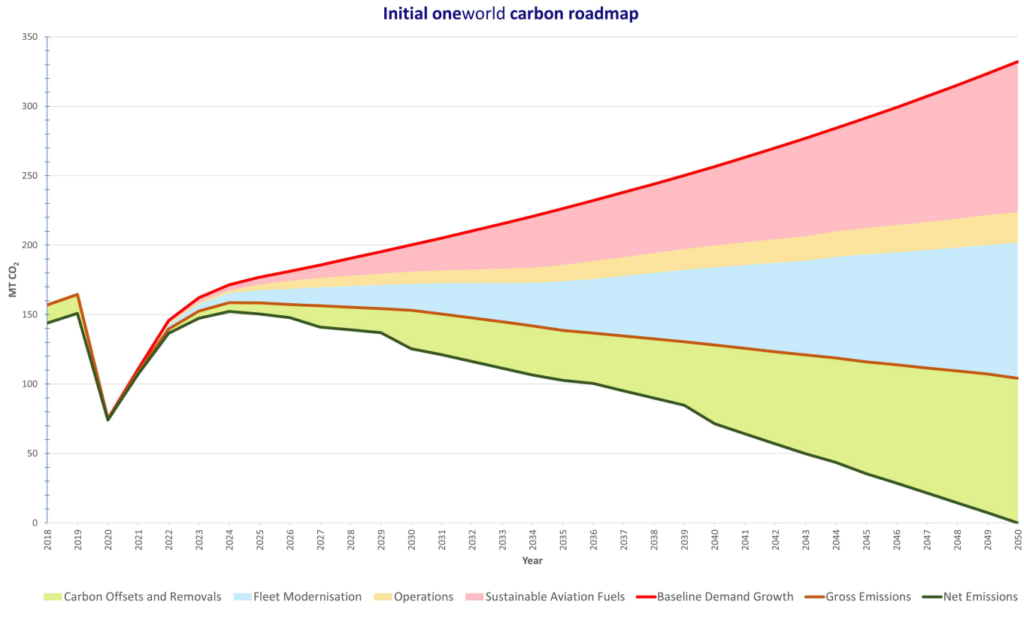

Oneworld’s Carbon Roadmap

Readers may remember learning about sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) and offsetting in my last article. Essentially, these two measures seem to be what big players in the aviation industry are adopting right now in order to cut emissions and work towards sustainability targets. CORSIA, the largest ever industry-wide offsetting agreement, seeks to stabilise emission levels at 2019 levels until new technology can be developed to begin phasing out carbon-based fuels. On that topic, carbon-neutral fuels like SAF are currently being adopted by more airlines and in larger quantities, in order to meet goals like this. In my opinion, airlines and alliances have a responsibility to advocate and implement the changes needed for a sustainable future. Progress will not be made until these players in the industry can unanimously agree that real change needs to happen now, and it needs to happen fast.

A great example of this can be seen in the efforts of alliances like OneWorld. Founded in 1999, OneWorld is aviation’s third largest alliance, incorporating 14 member airlines and serving 1000 airports in 17 countries. Using their influence over these member airlines, OneWorld is working towards various alliance-wide sustainability initiatives. CEO Rob Gurney is certainly keen to demonstrate the alliance’s sustainability goals, stating how “our member airlines are deeply committed to taking action to reduce emissions. This is a collective role we can play as an industry, and we hope our efforts will continue to create momentum in the journey towards decarbonising aviation.” Ambitious words, but how is OneWorld implementing its sustainability pledges? Well, that would be through the strategies developed by its environment and sustainability board. Chaired by Jonathon Counsell, the board has already implemented a variety of sustainable strategies for the alliance, such as joining the wider industry in pledging to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as well as supporting the Clean Skies for Tomorrow Coalition’s statement advocating 10% SAF usage by 2030. “Expanding the use of SAF is instrumental in the alliance’s pathway to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050,” OneWorld stated back in October, demonstrating a clear desire to incorporate SAF into their climate strategies. Combined with offsetting, OneWorld follow the current trend in sustainable aviation for using offsetting and SAF to work towards a carbon-neutral goal.

The Truth

A controversial COP26

SAF, offsetting. These certainly sound like positive measures for green flying. I bet you’re thinking that the industry already has it all figured out with these measures, and that the 2050 net-zero emissions goal is well within sight. If that’s the case, then I’m afraid I’ve got some bad news for you. You see, just like with most things in any business, it’s becoming more and more apparent that we don’t really have the full picture when it comes to these strategies. Most airlines want you to look at their climate strategies, read about all they’re doing to implement them, and praise them for their efforts, like I did earlier this year. You probably think they’re genuinely concerned about the environment – after all, how could they not be if they’re using SAF and offsetting? Let me give you the full picture, starting with offsetting. November saw COP26 held in Glasgow, a critical milestone to check the progress of measures agreed upon by the Paris agreement 5 years prior. Rather than being the peaceful ‘pat on the back’ many major players were expecting for an expected ‘job well done’, the conference saw massive protest, and controversy, over a few key issues.

I won’t get into everything that was discussed, but I will talk about the main controversial measure relating to aviation that came to light at the conference. This involves UN climate finance envoy Mark Carney’s creation of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero (GFANZ), and his plans for an offsetting ‘market’. Touted as the “gold standard for net-zero” by Carney (bit full of yourself there, mate), GFANZ has set out ‘science-based targets’ for its over 450 banks, insurers and asset managers to meet with their $130 trillion of capital. GFANZ’s analysis was almost immediately called into question by Reclaim Finance’s independent analysis, which concluded that it was “fundamentally flawed” and “lacks any criteria on fossil fuels or absolute emission reductions.” This became so apparent, that UN chief António Guterres felt the need to introduce a watchdog tasked with analysing net-zero emissions commitments from non-state corporations.

But how can this be? Surely a member of the UN knows what he’s doing? Oh, he does, and that’s precisely the problem. You see, Carney has decided on the creation of a ‘global offsetting market’ as the best possible way to reach GFANZ’s climate goals. COP26 proved to be a selling point for the scaling up of the offsetting task force, which includes airlines like EasyJet, responsible for the creation of the market. This would be all well and good, if offsetting was as effective as it seems on paper. A joint investigation by the Guardian and Greenpeace’s Unearthed group found that the majority of airlines greatly exaggerate the benefits of offsetting to passengers. An example of this can be seen in looking at where the funds from offsetting actually go. United Airlines, BA, and EasyJet have all been found to be ‘saving’ forests that weren’t actually under threat. An offsetting project in the Peruvian Amazon backed by EasyJet was also found to be run by a couple of logging companies that are active in the forest’s deforestation.

Greenpeace’s investigation found no evidence that offsetting schemes are backed up by carbon savings, with the corporation stating that the new offsetting market simply allows banks and billionaires to make millions off the climate crisis. Even the experts have started to weigh in on offsetting – “Most of this is pure public relations,” states Philip Fearnside, an ecologist at the National Institute for Research in Amazonia. “Neither planting trees nor avoiding deforestation will make a flight carbon-neutral,” claims Britaldo Silveira Soares Filho, a professor and expert on deforestation. On top of all this, offsetting actually allows companies and airlines to simply keep on polluting, with the excuse that they’re tackling climate change.

There’s a name for stuff like this: greenwashing – when a company or state hides behind a façade of helping the environment, when in reality they’re doing the opposite. It’s not just organizations like Greenpeace (who don’t exactly have the most respected reputation) trying to expose the less-than-stellar effects of offsetting. Guterres, in a very telling statement, lamented that while the agreement on the offsetting market “takes important steps”, the conference failed to achieve the goals set out in the Paris agreement – namely, ending fossil fuel subsidies, phasing out coal, putting a price on carbon, building the resilience of vulnerable communities, or fulfilling the commitment of $100 billion in climate finance to support developing countries. In another dramatic turn of events, Greenpeace actually offered a rather viable and fair alternative to offsetting ‘greenwashing’. They posed a tax on excessive flying in order to contain the demand for flights. This, in my opinion, would actually be more effective than offsetting. While it may be hard to admit, the evidence and facts clearly point to the only solution being to limit the number of flights until new, sustainable energy can be used to power air travel

SAF – sustainable, but is it feasible?

Atmosfair’s SAF producing factory

So, the future is in new tech then. Enter SAF. It makes sense that a biofuel with ‘sustainable’ in its name would be the answer to the industry’s carbon worries, right? Well, yes and no. SAF is a great intermediary fuel for an industry looking to phase out carbon-based fuels, as it can be mixed with these fuels to reduce the amount of them used per flight. There is, however, a massive problem with SAF – there isn’t enough of it. Only 4% of the total aviation fuel produced per year is SAF, owing to the fact that it is expensive to manufacture. A tonne of fossil-based fuel costs around $675 to make, compared to the minimum $1,069 it costs to make the same amount of SAF. On top of this, there is a limited amount of biological biomass available to dedicate to making SAF, as it enters into competition with sustainable fuels made from the same sources for road transport. There’s also the origin of the biomass used to make the fuel to think about. For example, fuel made from palm oil biomass (one of the worst mono-crops for the environment) is going to be less sustainable than fuel made from recycled compost. Adopters of SAF have to compare heightened costs and a limited supply to fossil-based fuels which are cheaper and come with extensive infrastructure in place for their use.

Production of SAF does seem to be increasing, however. Plants like Atmosfair’s dedicated SAF production site in northern Germany are slowly becoming more and more popular. The plant creates E-kerosene from electricity generated through ‘green-hydrogen’ (more on that later). Taking SAF production one step further, the plant mixes the fuel it produces from renewable means with conventional kerosene and transports it to nearby Hamburg Airport for use, streamlining the process. E-kerosene itself is a special kind of SAF, one with the capabilities to power jet engines all by itself. This fuel, therefore, may be the golden ticket the aviation industry is looking for in transferring away from fossil fuels. With Germany aiming to have 2% of its aviation industry’s 10 million ton per-year kerosene usage coming from SAF by 2030, it’s plants like these that will help put a dent in a global SAF shortage.

There are still, however, a few drawbacks. E-kerosene itself is around 4-5x more expensive than conventional kerosene and is only 100% sustainable if you use more expensive sustainable methods to create it. If you want to make money, it’s a no brainer which fuel you should go for, and that has meant that, despite production gradually increasing, and more airlines adopting the fuel, SAF is still far from being any kind of solution to the industry’s climate troubles. “We still do not produce enough renewable energy. So, we have to decide: do we want to use precious green energy for essential things or for luxury activities of a global minority?” states Manuel Grebenjak, campaigner at Stay Grounded. This leaves us with the same problem – if we want to seriously limit carbon emissions from aviation as fast as possible, the only solution seems to be to limit flights.

Going green with Greenliner

Change does indeed take time, and I agree with the plans of CORSIA: to implement short term strategies to minimise climate impact while new technology is developed that enables us to stop using fossil fuels for good. So, how is aviation accomplishing this? We’ve already seen that economic measures like offsetting, as well as alternative fuels like SAF, aren’t as effective as we might like to hope they could be. However, it Is also unlikely that the entire global aviation industry will decide to just lose more money after a pandemic and limit flights around the world. In my opinion, then, a combination of both heightened usage of SAF and more regulated offsetting seems to be the best immediate strategy aviation has right now while we wait for new tech to be developed.

Initiatives like Etihad’s Greenliner’ provide us with examples of how manufacturers and airlines are partnering up to make the most of SAF and offsetting, while also testing and developing new sustainable tech. Launched in 2019, the partnership programme between Boeing and Etihad sees a special 787-10 tapped for operation in Etihad’s fleet. The craft is not only eye-catching with its special green livery but it also routinely operates ‘eco-flights’, the most recent being this year, which saw an Abu Dhabi to Heathrow route flown on 38% SAF with 100% of the flight’s emissions fully offset. On top of this, the flight saw a trial of UK firm Satavia’s ‘DECISIONX:NETZERO’ system (sounds like something out of the Matrix!). The firm claims its software can eliminate as much as 60% of aviation’s total climate impact by mitigating the effect contrails have on the environment. Combined with a modern fuel-efficient fleet, weight reductions on flights, and partnerships with companies like Siemen’s to produce green hydrogen, Etihad is well on its way to achieving its net emission reduction of 50% for 2035. The airline is demonstrating to the industry that it is possible to use a combination of SAF and offsetting with increasing frequency to at least limit the number of further emissions pumped into the atmosphere, while developing new sustainable tech at the same time.

The future is hydrogen

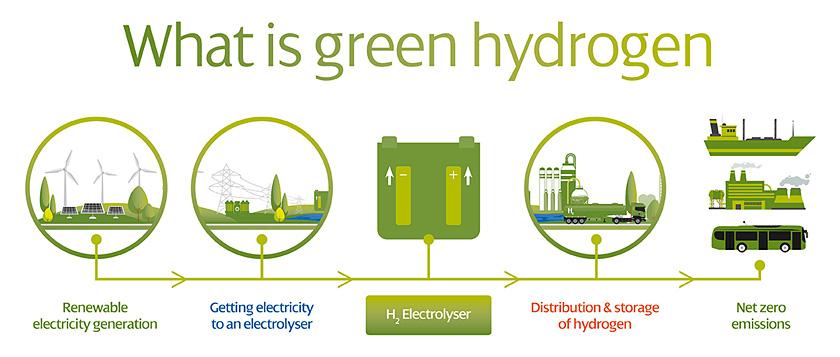

Green Hydrogen is looking like the sustainable fuel of the future

Speaking of sustainable tech, a lot of progress is being made in the development of aircraft which use completely different, green fuel sources instead of the standard fossil fuels. No blended SAF or offsetting will be needed for these futuristic designs, and in my honest opinion, they signal the start of a new era in aviation – one of green flying. Hydrogen seems to be the top contender for an alternative fuel source at the moment, with manufacturers rushing to be the first to develop a working concept aircraft that runs entirely on the fuel source. There’s an absolute killing to be made by whoever gets there first, as they’ll not only be able to corner a new market, but really set the tone and pace of development for the near future. But why hydrogen? There are a few good reasons. Hydrogen creates no emissions, for a start, and that already makes it a pretty good contender for an alternative to fossil fuels. It also has around three times as much energy as fossil fuels, meaning it’s more cost and energy-efficient. So why isn’t the industry already using this wonder fuel? There are, admittedly, a few major drawbacks.

The current way hydrogen is mass-produced is an incredibly polluting process, causing nearly as many emissions over its lifetime as it saves. In fact, 95% of the world’s produced hydrogen is made this way, giving it the name ‘brown hydrogen’. There are, however, alternatives to this. Blue hydrogen is made using the same processes but includes carbon capture and storage in its production, reducing its overall emissions. Hydrogen made using this method equates to around 4% of the world’s production, and while it may be less polluting than brown hydrogen, still creates emissions. Then we have green hydrogen. Easily the best alternative to fossil fuels, green hydrogen is made from renewable energy, meaning that it is 100% emission-free over its lifetime. However, owing to the lack of infrastructure and the limited amount of renewable energy available for its production, it is incredibly expensive to make, causing it to be much less appealing to an industry prioritising profit over everything else. Again, the issue of cost seems to play the biggest role in explaining why already available green fuels are not being scaled up and immediately adopted by airlines.

There, is, however, some good news on this front, and it comes from a very unlikely source: oil and gas companies (yes, you heard that right!). These organisations have finally begun to accept the inevitable and realise that fossil fuels won’t be king for much longer. Because of this, in a bid to stay relevant in the future, companies like Shell have started to heavily invest in the manufacture of green hydrogen, scaling up the technology needed to mass-produce the fuel. “Shell is particularly excited about hydrogen as an energy vector as we see it can reach all those parts of the energy system that are really hard to electrify directly,” stated Paul Bogers, Vice President of hydrogen at the company. Governments too, with their newfound net-zero targets, have dumped huge sums of money into the same R and D needed to make green hydrogen the fuel of the future.

Speaking of sustainable tech, a lot of progress is being made in the development of aircraft which use completely different, green fuel sources instead of the standard fossil fuels. No blended SAF or offsetting will be needed for these futuristic designs, and in my honest opinion, they signal the start of a new era in aviation – one of green flying. Hydrogen seems to be the top contender for an alternative fuel source at the moment, with manufacturers rushing to be the first to develop a working concept aircraft that runs entirely on the fuel source. There’s an absolute killing to be made by whoever gets there first, as they’ll not only be able to corner a new market, but really set the tone and pace of development for the near future. But why hydrogen? There are a few good reasons. Hydrogen creates no emissions, for a start, and that already makes it a pretty good contender for an alternative to fossil fuels. It also has around three times as much energy as fossil fuels, meaning it’s more cost and energy-efficient. So why isn’t the industry already using this wonder fuel? There are, admittedly, a few major drawbacks.

The current way hydrogen is mass-produced is an incredibly polluting process, causing nearly as many emissions over its lifetime as it saves. In fact, 95% of the world’s produced hydrogen is made this way, giving it the name ‘brown hydrogen’. There are, however, alternatives to this. Blue hydrogen is made using the same processes but includes carbon capture and storage in its production, reducing its overall emissions. Hydrogen made using this method equates to around 4% of the world’s production, and while it may be less polluting than brown hydrogen, still creates emissions. Then we have green hydrogen. Easily the best alternative to fossil fuels, green hydrogen is made from renewable energy, meaning that it is 100% emission-free over its lifetime. However, owing to the lack of infrastructure and the limited amount of renewable energy available for its production, it is incredibly expensive to make, causing it to be much less appealing to an industry prioritising profit over everything else. Again, the issue of cost seems to play the biggest role in explaining why already available green fuels are not being scaled up and immediately adopted by airlines.

There, is, however, some good news on this front, and it comes from a very unlikely source: oil and gas companies (yes, you heard that right!). These organisations have finally begun to accept the inevitable and realise that fossil fuels won’t be king for much longer. Because of this, in a bid to stay relevant in the future, companies like Shell have started to heavily invest in the manufacture of green hydrogen, scaling up the technology needed to mass-produce the fuel. “Shell is particularly excited about hydrogen as an energy vector as we see it can reach all those parts of the energy system that are really hard to electrify directly,” stated Paul Bogers, Vice President of hydrogen at the company. Governments too, with their newfound net-zero targets, have dumped huge sums of money into the same R and D needed to make green hydrogen the fuel of the future.

The designs of the future

Airbus leads the charge in sustainable aviation designs

Manufacturers have really taken the potential of this new fuel in their stride. Projects like Airbus’ ‘ZEROe’ concept demonstrate what the future of aviation could look like with hydrogen. With aims to develop the “world’s first zero-emission commercial aircraft” by 2035, Airbus released three interesting hydrogen-powered concepts back in 2020. Utilising hydrogen combustion through modified gas turbine engines, Airbus’ concepts are built around the premise of using both hydrogen fuel cells as well as liquid hydrogen. Touting both a ‘Turbofan’ (most similar to current commercial jets), with 200 passenger capacity, and a ‘Turboprop’ (a smaller, prop-driven aircraft, with a capacity of 100), Airbus’ standard concepts feature 2000 and 1000nm ranges respectively. That’s good enough for most medium-haul routes but comes up short of servicing most commercial long-haul routes. The question of range is quite a big one, which modern hydrogen designs don’t seem to have an answer for. This will presumably not be an issue with advancements in tech, but with initial designs like ZEROe not set to become a reality until at least 2035, we may have a long wait ahead of us before long-haul hydrogen craft become a reality. Airbus also have a third, blended wing hydrogen concept, which has a few distinct advantages over standard aircraft designs. More interior space and increased fuel efficiency are the two big ones, facilitated by the more aerodynamic design. I always get excited over new aircraft concepts and, in my opinion, the more futuristic the better. 2035 is a long way off though, and we may see competitors coming up with new, more advanced concepts by then.

Congrats on getting this far! I know it’s been quite a bit of information to take in, but I hope you now see the importance of being up to date on the big sustainability question facing the aviation industry. I’m not going to lie, we all face a huge challenge in modernising a very polluting industry for a future of green flying, but if we want to save this planet, it’s very, very necessary. Between technological advancements and the increasing adoption of sustainable measures, I truly believe aviation can achieve the ambitious sustainability goals it has set for itself. That is, if we don’t fall for the trap of once again prioritising quick profit over long term sustainable income.

0 Comments